treasury

An archive filled with treasures. Unexpected documents. Stories. Memories. History. You can read about the most remarkable items of our collection here on the website. Hopefully these will entice you to come pay us a visit. To investigate your family history. To track down the original owners of the house you live in. To research law and jurisdiction in the 19th century. With our 18 kilometers worth of archival documents, you will surely find answers to many of your questions.

An archive filled with treasures. Unexpected documents. Stories. Memories. History. You can read about the most remarkable items of our collection here on the website.

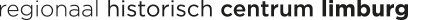

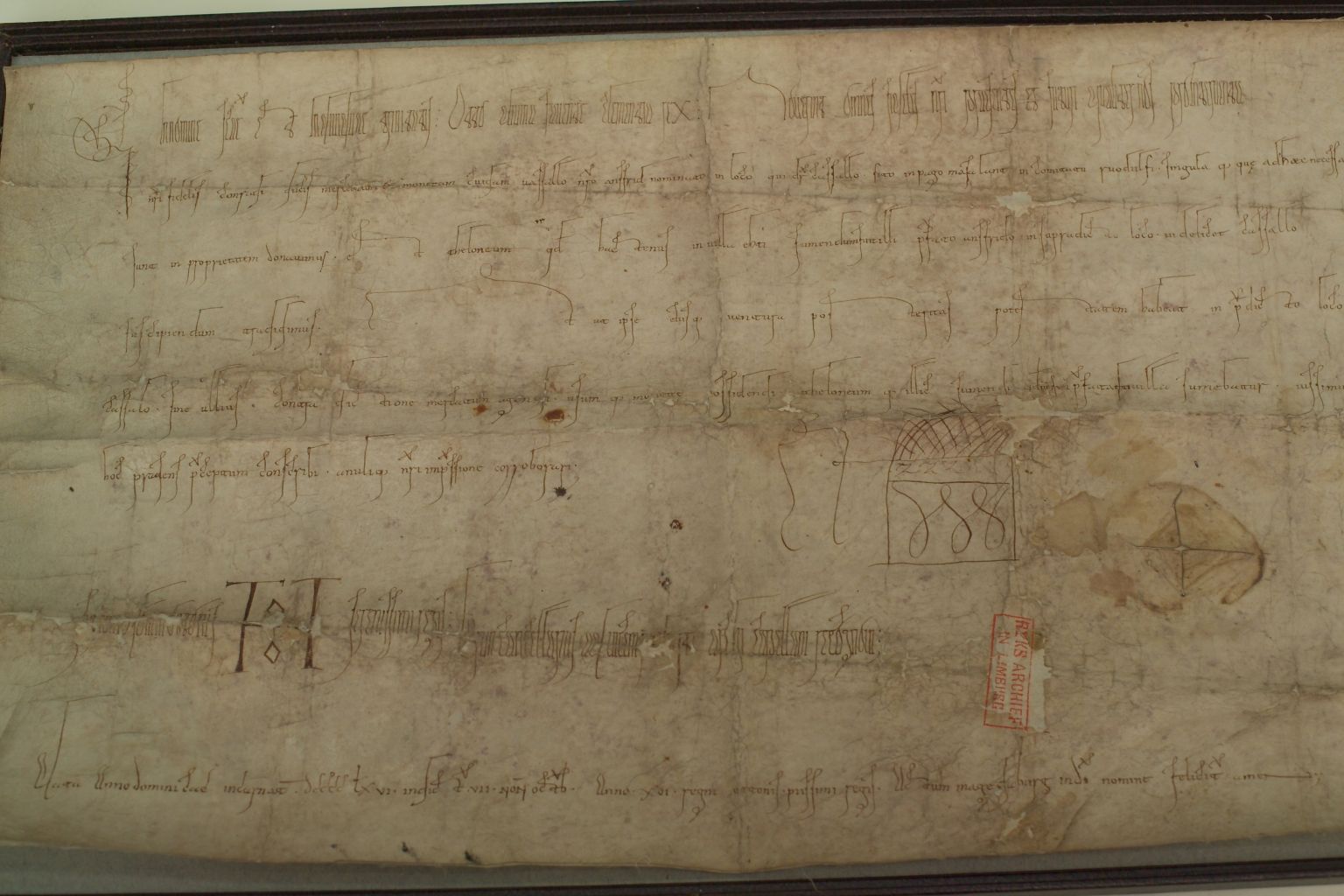

The oldest document: Document wherein King Otto I granted the feudal rights of Kessel and Echt, 950. Thorn abbey archive.

The oldest document

Document wherein King Otto I granted the feudal rights of Kessel and Echt, 950

Thorn abbey archive.

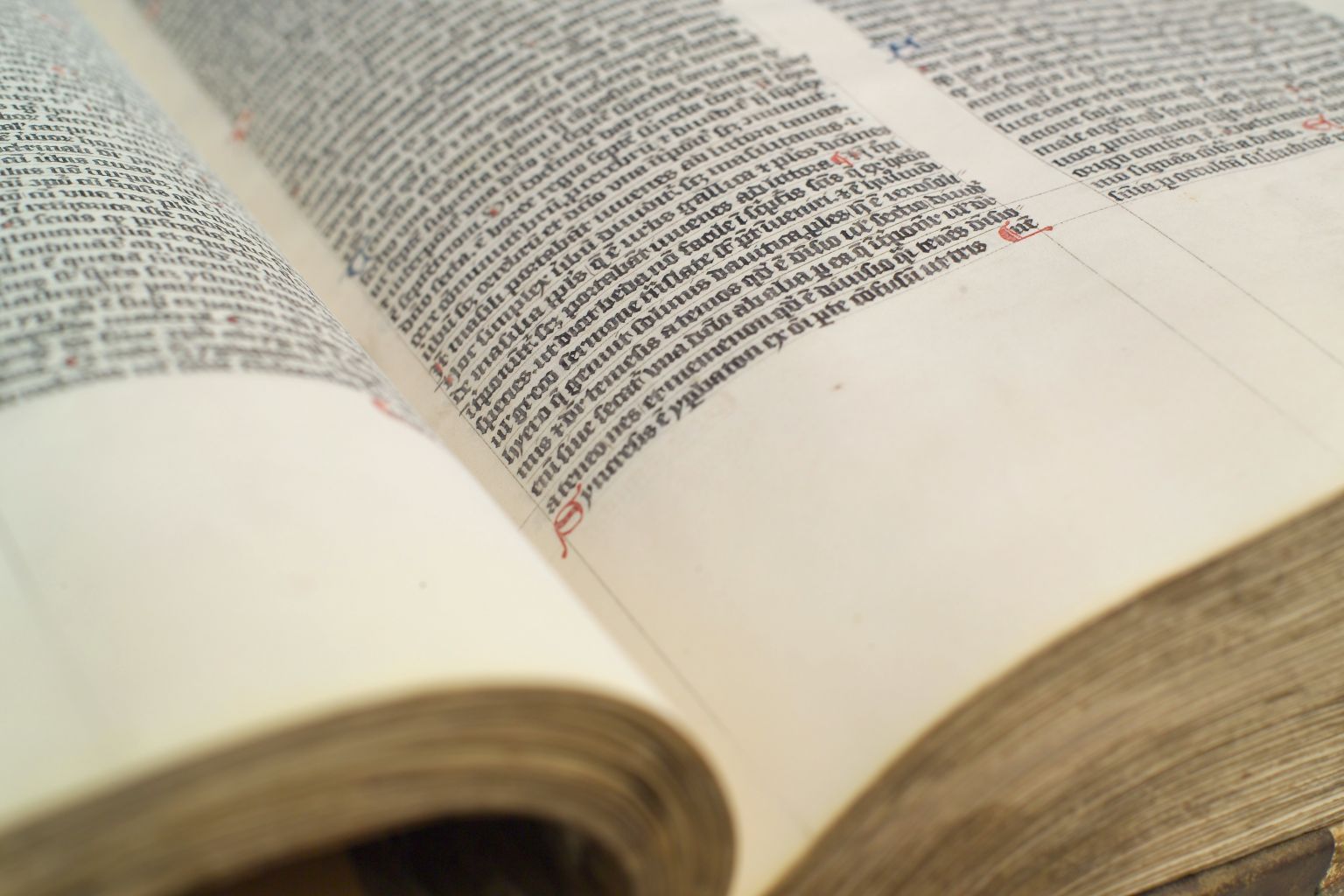

The deed from October 7, 950, whereby 'German' King Otto I granted his feudal rights of Kessel and Echt to Ansfried, is the oldest document that is kept in an archive in the Netherlands. There are even older charters, that concern regions of present-day the Netherlands, however these are located in foreign archives. Although... is this really the oldest archive of the Netherlands? It is after all only an imitation of the original. Still, the answer is yes. It is and remains the oldest document, because the fabrication was produced not much later, still in the tenth century. The deed was placed in the Thorn abbey because Ansfried eventually passed the rights once granted to him, on to this abbey he himself founded.

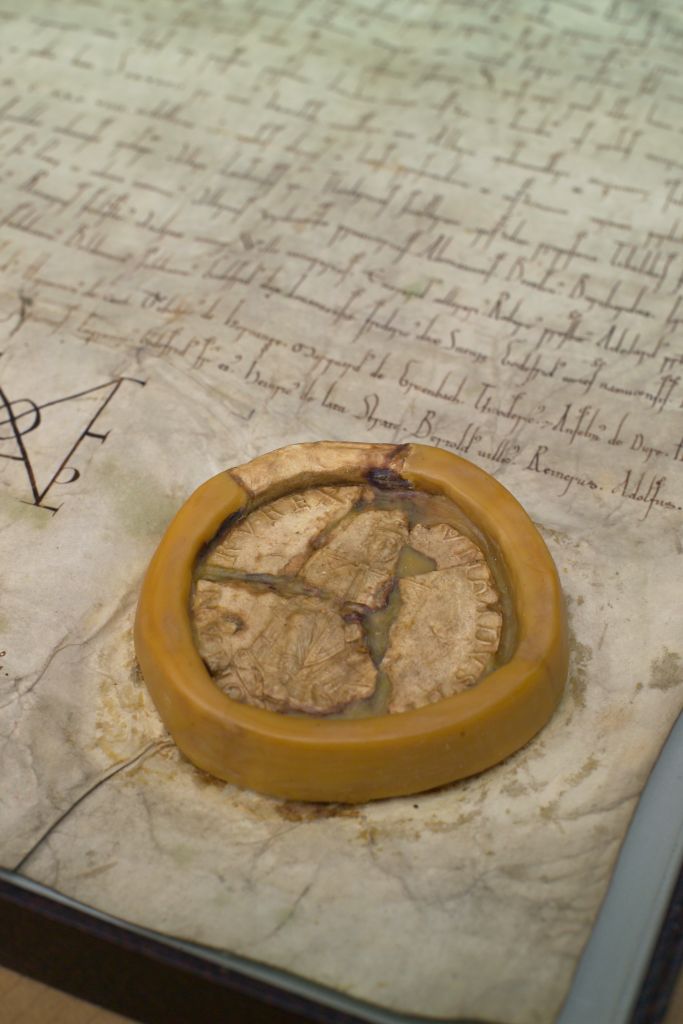

The oldest bridge: Charter of Conrad III, 1139. Chapel archive of Saint Servaas.

The oldest bridge

Charter of Conrad III, 1139. Chapel archive of Saint Servaas.

The oldest bridge of Maastricht, and also that of the Netherlands is called the 'Sint-Servaas' bridge, because it belonged to the canons of Saint Servaas in the Middle Ages. This deed of the King Conrad III of the Holy Roman Empire from 1139, that was safe-guarded in their archive, is the deed of donation. The canons were allowed to demand a toll for crossing, but were also responsible for the maintenance of the bridge.

The smallest letters: Bible, 13th or 14th century. Manuscript collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

The smallest letters

Manuscript collection GAM.

Also this Latin Bible comes from Koblenz, namely from the Jezuit monastery. The delicate gothic script with illuminate lettering is so small and at the same time so perfect, especially in comparison to the Catholicon mentioned below, that it seems almost impossible that this was achieved without the aid of a magnifying glass. The unusually soft and fine quality parchment used is most probably made from lambskin, maybe even that of an unborn lamb.

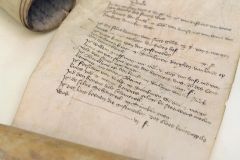

The longest register: Tax roll of the Einrade Court in Holset, 14th century. Archive St. Lambertus parish Holset.

The longest register

Tax roll of the Einrade Court in Holset, 14th century. Archive St. Lambertus parish Holset.

The parish archives of Limburg can be found in each region, in the municipal archives of Venlo, Weert, Roermond and Sittard-Geleen. The parish archives of Maastricht and the Heuvelland are located in the RHC Limbug. The unique piece pictured here has its origins in the Sint-Lambertus Church in Holset. It is a fourteenth-century rent and tax register belonging to the Einrade Court. These property taxes were fixed, to be paid on a yearly basis. This item is particularly interesting for local historians as it contains much information such as the names of individuals, family names and field names in the villages of Vijlen, Vaals, Gemmenich, Gulpen and the adjoining communities. In addition to its old age and content, this archive is particularly unique: it is a continuous roll of sewn-together sheets of parchment.

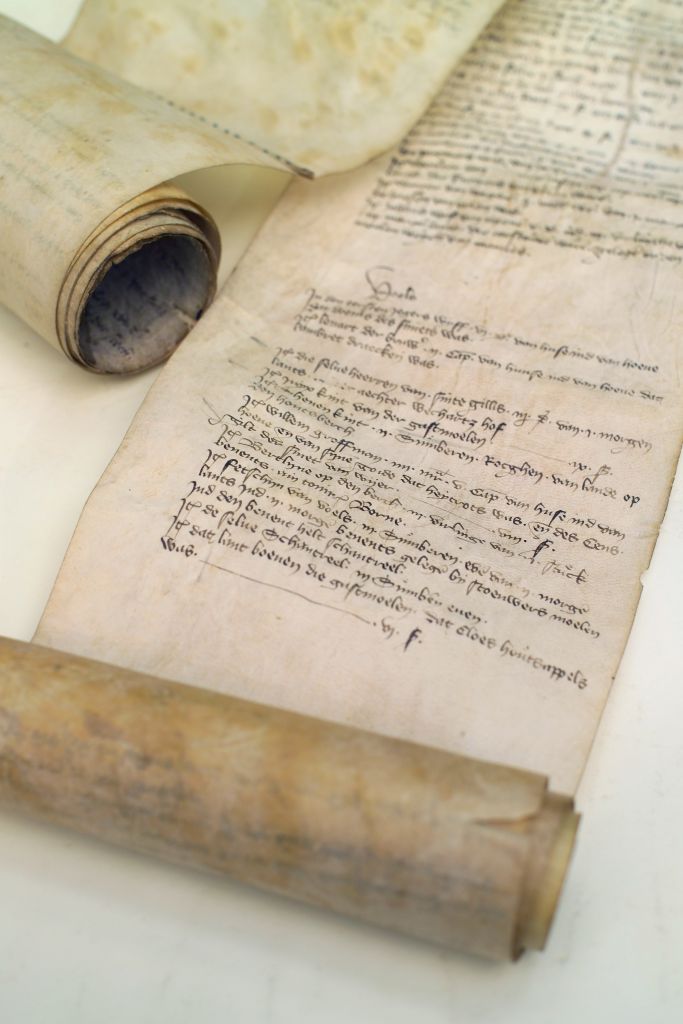

The largest book: Joannes de Ianua, Catholicon, 1437. Handwriting collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

The largest book

The largest book: Joannes de Ianua, Catholicon, 1437. Handwriting collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

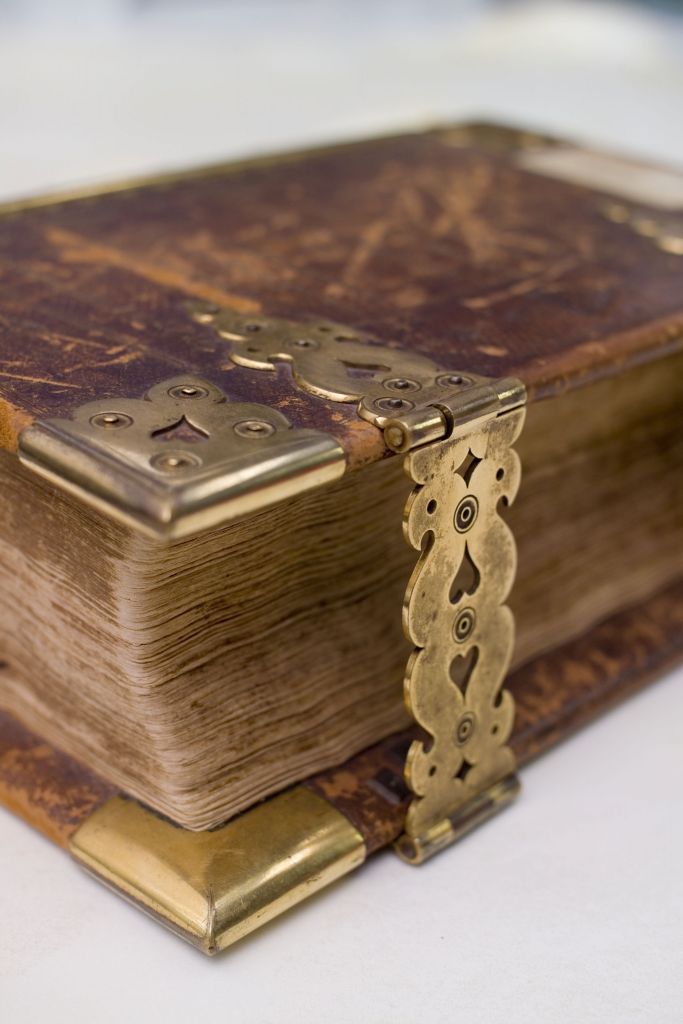

This enormous book, weighing many kilos, is an ethymological lexicon, titled 'Catholicon'. The author of this scientific work from the thirteenth century is the preacher, Joannes de Ianua of Genua. Two centuries later, it was copied by a monk in frail gothic script on parchment, and finished off with decorative initials and bordering. The binding consists of the usual leather covered wooden slats - in this case wooden boards as far as size and thickness are concerned - complete with copper mounting. In 1437, the book was donated by Joannes de Monte to his monastery in Koblenz.

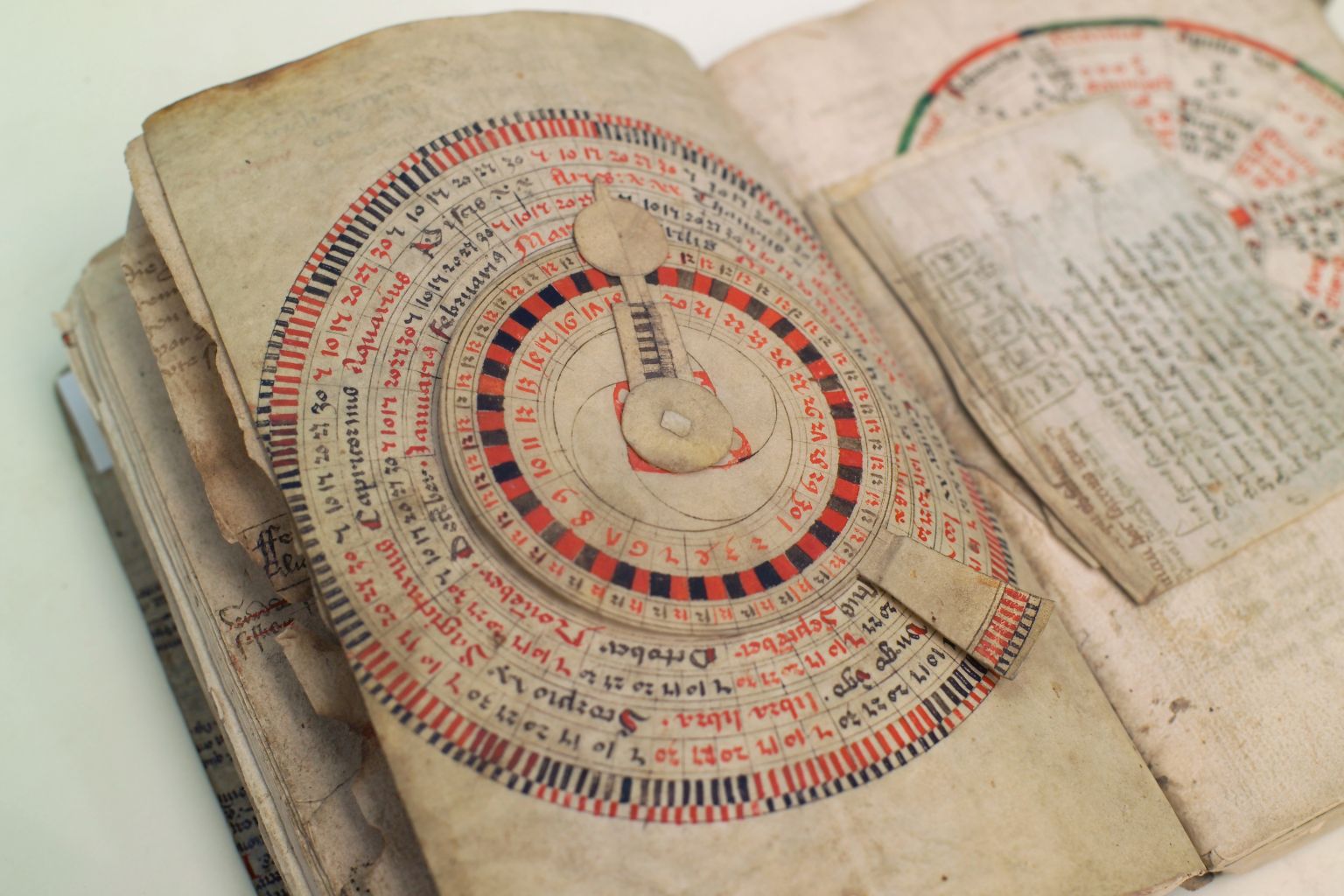

Calendar, tropics and zodiac: House book of the Houcken family, around 1450-1500. Manuscript collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

Calendar, tropics and zodiac

House book of the Houcken family, around 1450-1500. Manuscript collection GAM.

The house book of the Houcken family from the bishopry of Munster is very diverse as far as the content is concerned. It contains various calendars that relate to the signs of the Zodiac, the tropics around the globe and the human body. Other sections include ‘Speculum medicorum’, a copy of a letter from Pope Leo to ‘koninch Charle doen hij ten strydt soude ryden om hem daarmede te beschermen’ ('king Charle when he went to battle to protect him’), a Munster chronical from the years 1408-1449 and genealogical notes of the family itself.

A book with copper locks: House book of the Houcken family, around 1450-1500. Manuscript collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

A book with copper locks

House book of the Houcken family, around 1450-1500. Manuscript collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

Since the sixteenth century, the four 'deciding commissioners' were representatives of the two rulers of Maastricht, two of the Duke of Brabant and two of the Bishop of Luik. Once every two years, these ambassadors would come to Maastricht to take care of administrative and judicial matters (usually in appeal). There resolutions were stipulated in the pictured book. Many of these decisions were made law and then collected in our very own law book of Maastricht, the 'Recueil der Recessen', that has been reprinted many times.

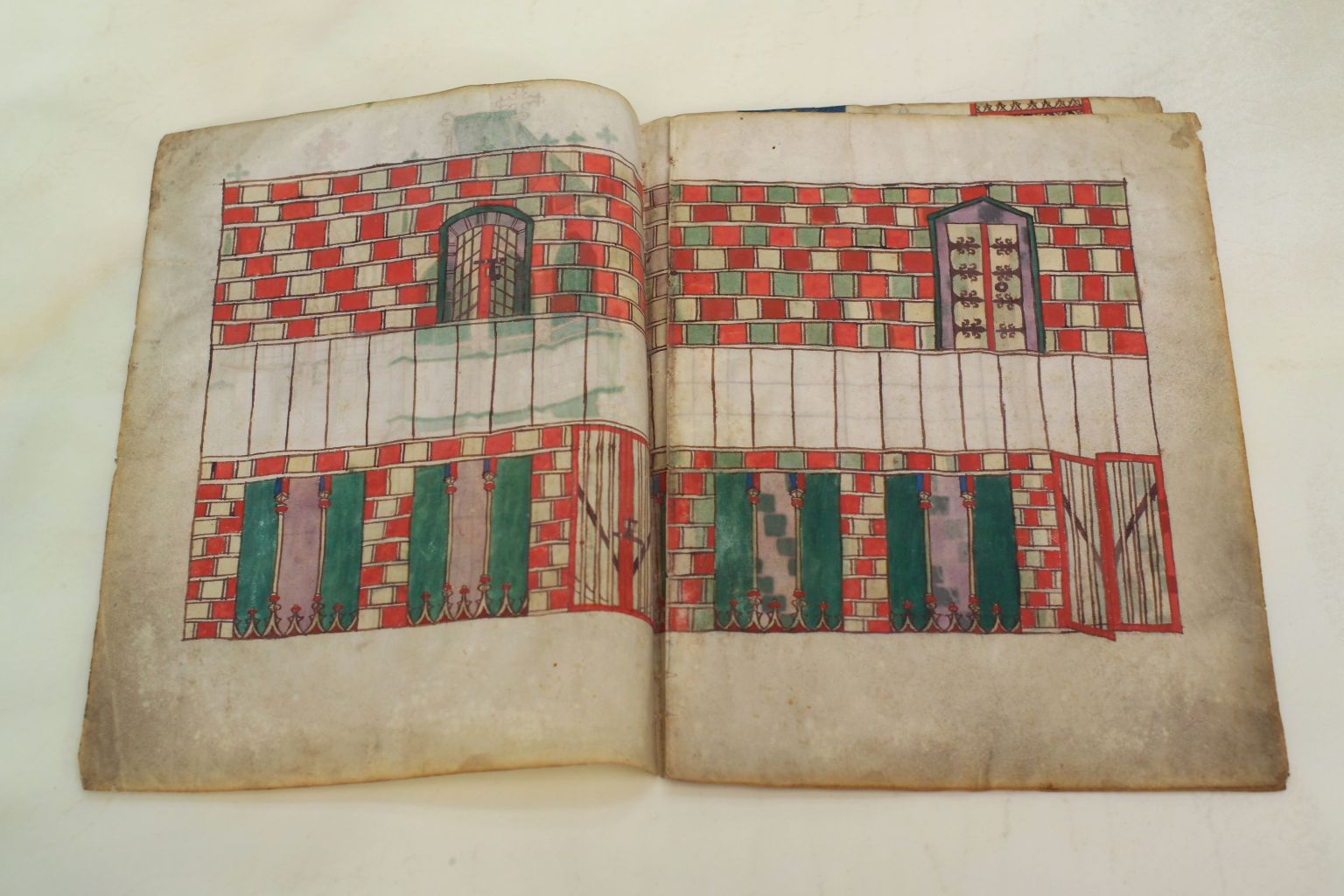

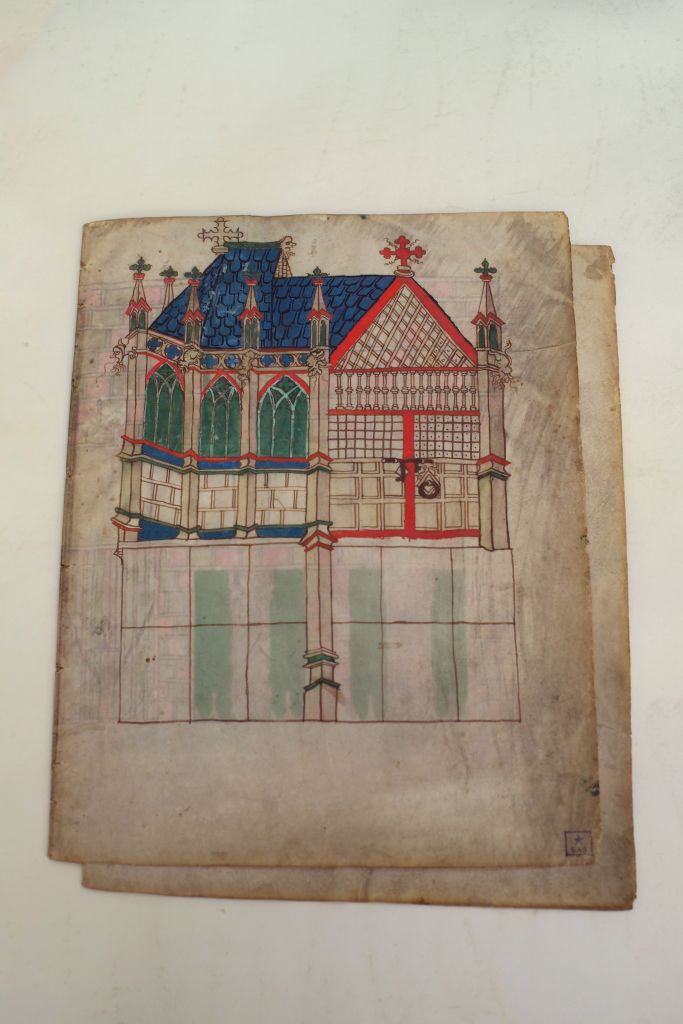

The oldest drawing (1): Blueprints for the Sint-Servaas Church in Maastricht on parchment, around 1460. Drawings and prints collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

The oldest drawing (1)

Blueprints for the Sint-Servaas Church in Maastricht on parchment, around 1460. Drawings and prints collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

In 1461 King Lodewijk XI of France ordered for 1200 kroner to be paid to the Sint-Servaas canons to contribute to the costs of building a new chapel. This addition was built in the gothic style at the northern side of the absis on the Vrijthof and was named the 'Koningskapel' or King's Chapel. In 1804, in the French Period, the Koningskapel was torn down. This drawing, being the oldest drawing at the RHC Limburg is also thought to be the oldest drawing that features a building of Maastricht. In fact, it is a blueprint on parchment, where not only the Koningskapel, or King's Chapel, can be seen, but also the planned construction of a statue of Sint Servaas and the interior of the halls. The halls are illustrated from a birds-eye point of view, where the floor is in the center and the walls are drawn as if they were folded outwards to lay flat, in line with the floor.

The oldest drawing (2): Blueprints for the Sint Servaas Church in Maastricht on parchment, around 1460. Drawings and prints collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

The oldest drawing (2)

Blueprints for the Sint Servaas Church in Maastricht on parchment, around 1460. Drawings and prints collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

As a matter of fact, the oldest drawing of the RHCL is a blueprint on parchment, where not only the Koningskapel, or King's Chapel, can be seen, but also the planned construction of a statue of Sint Servaas and the interior of the halls. The halls are illustrated from a birds-eye point of view, where the floor is in the center and the walls are drawn as if they were folded outwards to lay flat, in line with the floor.

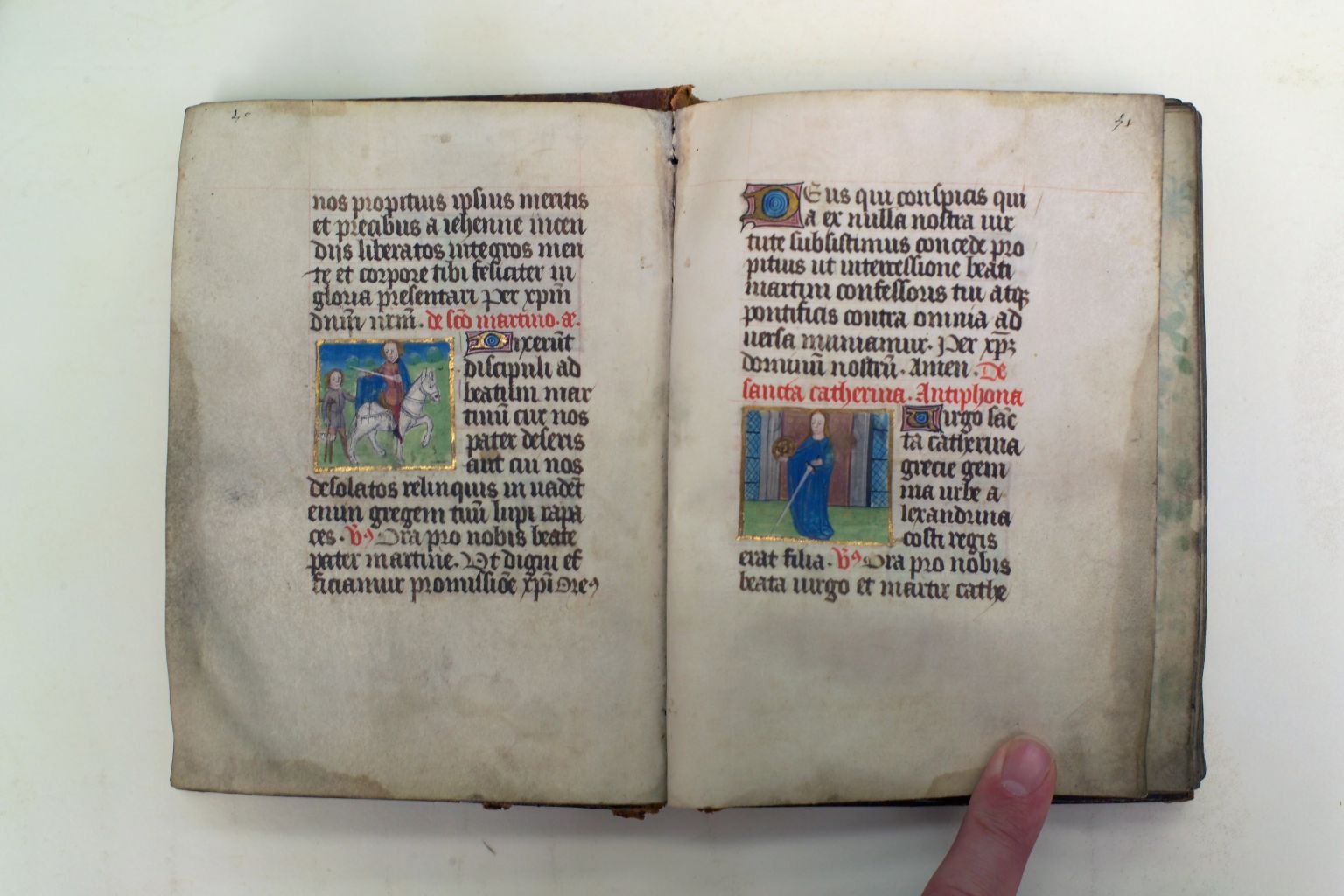

The work of monks: Breviary, around 1500. Manuscript collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

The work of monks

Breviary, around 1500. Manuscript collection GAM.

This delicate sample of the work of monks, a breviary from around 1500, comes from one of the many monasteries that could be found in Maastricht at the time. It is hand-written on parchment, in Latin, and illustrated with eleven full-page miniatures with biblical scenes and twelve smaller miniatures with representations from the lives of Saints. One of these twelve is an image of Saint Martinus of Tours, who shares his cloak with a beggar.

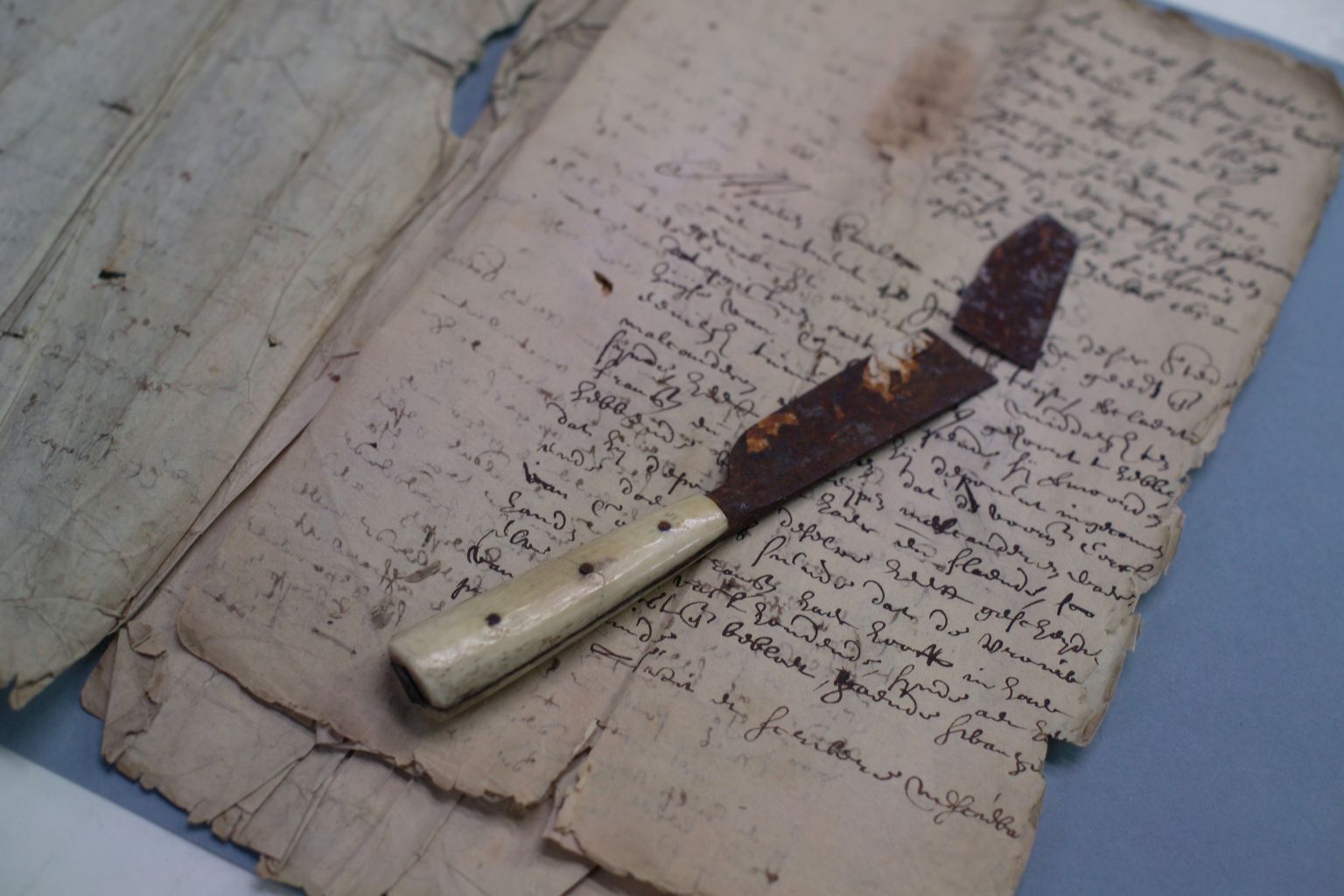

A knife as evidence: Case with knife. Brabants High Court archive Maastricht.

A knife as evidence

Case with knife. Brabants High Court archive Maastricht.

These case specimens from (...) concern an argument that got out of hand, involving two men and a woman. It came to blows when the woman grabbed a kitchen knife and began stabbing one of the men so fiercely that the point of the knife broke off. The knife was used as ‘corpus delicti’ in the lawsuit and kept as evidence with the case file. Not yet researched, is whether or not the brown color of the knife is only caused by rust. It is suspected that there are also traces of clotted blood here.

Executioner's sword and pillory (1): Criminal case Jehenne Goffin, 1656. Brabant High Court archive of Maastricht.

Executioner's sword and pillory (1)

Criminal case Jehenne Goffin, 1656. Brabant High Court archive of Maastricht.

The case against the slandering Jehenne Goffin in 1656 was apparently quite long-winded, because the secretary made a real work of art out of the pillory he drew on the case file. In the eighteenth-century, the pillory of Maastricht was positioned next to the City Hall. Whoever was being put to shame looked from that spot directly into the street the 'Grote Gracht'. Standing shamefaced at the pillory in that time was also referred to by the locals in Maastricht's dialect as 'De Groete Grach oploere', meaning peering onto the Grote Gracht. The gallows of the co-ruled Maastricht were located in Wyck, on the side nearest to the village of Heer. The gallows of Vroenhof were on the Dousberg.

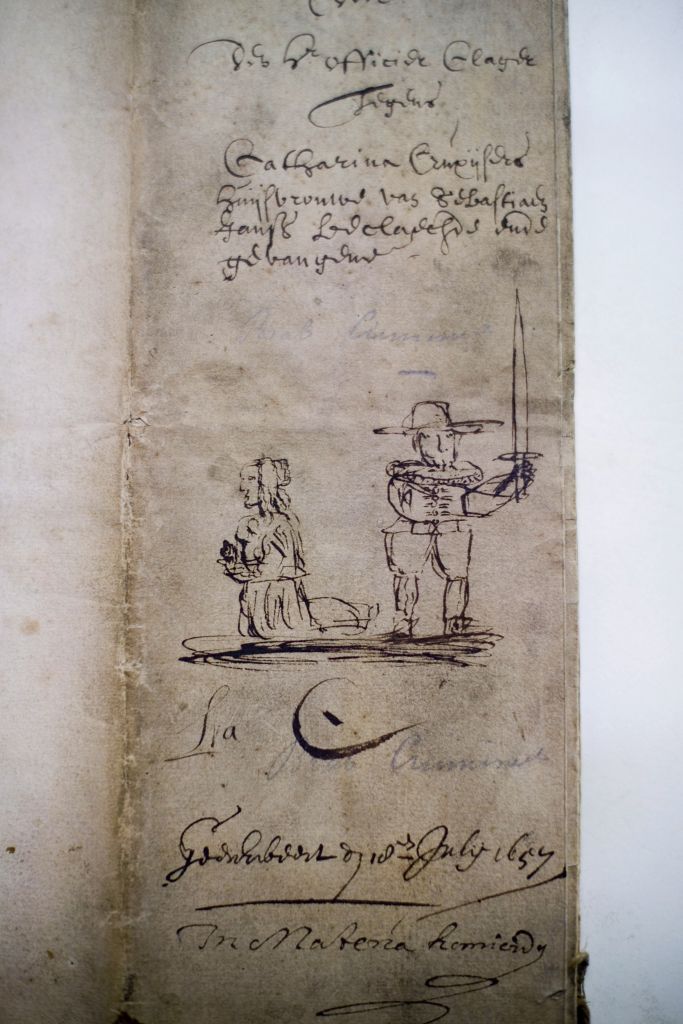

Executioner's sword and pillory (2): Criminal case Catharina Cruxijsers, 1657. Brabant High Court archive of Maastricht.

Executioner's sword and pillory (2)

Criminal case Catharina Cruxijsers, 1657. Brabant High Court archive of Maastricht.

For many criminal cases that took place in Maastricht, you will find a small, simple sketch on the outside of the bundle of case files, featuring either the gallows, a wheel, a sword or a pillory to indicate which punishment was due or if a sentence was declared. Such a sketch can also be found here -although somewhat more elaborate than usual- regarding the case of Catharina Cruxijsers, who was beheaded by executioner's sword for the murder of her baby daughter in 1657.

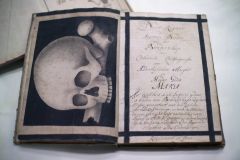

Ever-present death (1): List of deceased members of the brotherhood of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, 1721-1868. Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe parish archive Maastricht.

Ever-present death (1)

List of deceased members of the brotherhood of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, 1721-1868. Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe parish archive Maastricht.

Nowadays, people tend to view death as something that only comes after life, something to worry about later, something to put off as long as possible and that is not to be discussed until the moment arrives. On the contrary, people in the middle ages considered death as inseparable from life. That people still believed this in the eighteenth-century is apparent from the frontal image of a skull in the list of the 'Deceased Brothers' of the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe brotherhood in Maastricht.

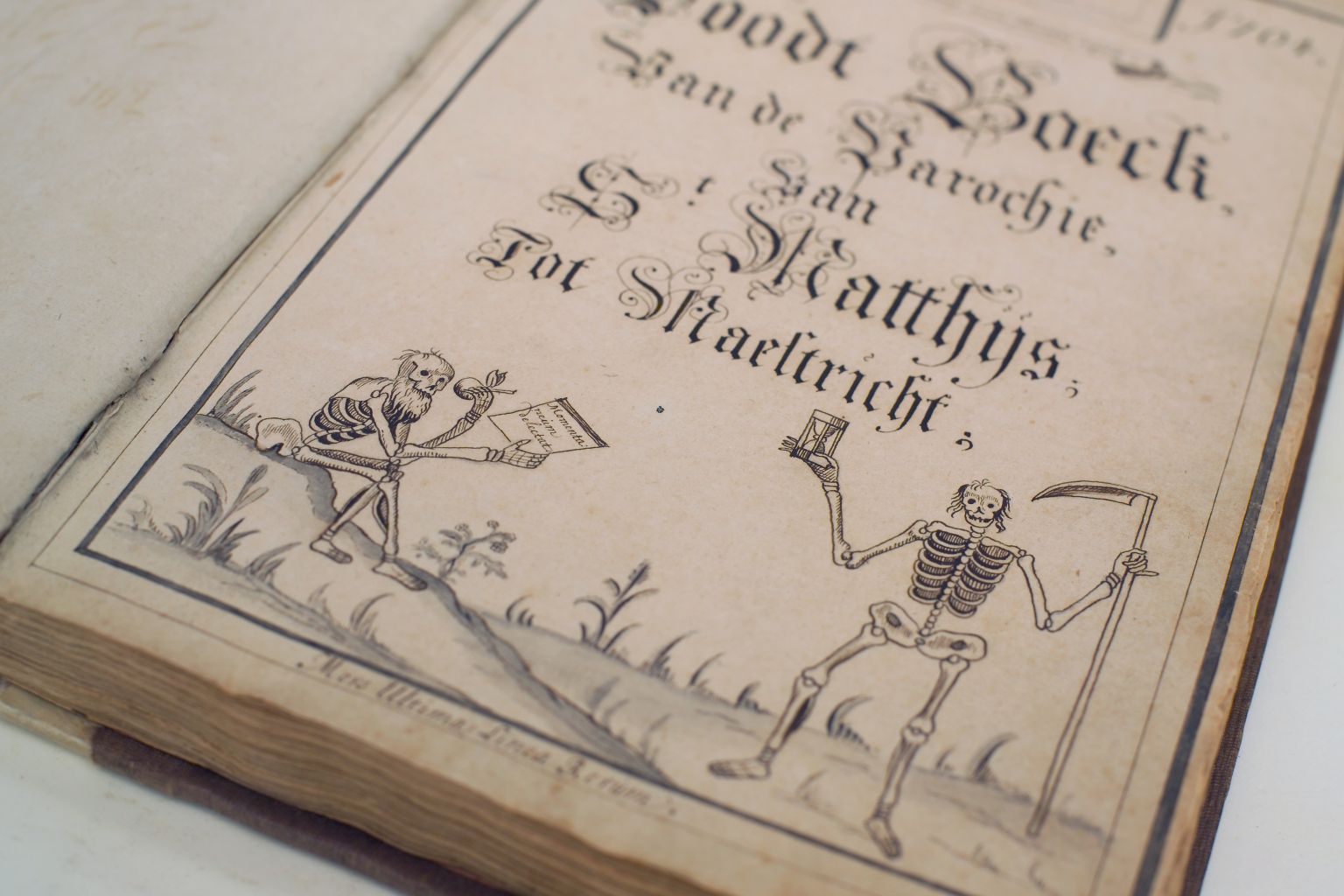

Ever-present death (2): Burial register Sint-Matthias parish Maastricht, 1704-1747. DTB Maastricht.

Ever-present death (2)

Burial register Sint-Matthias parish Maastricht, 1704-1747. DTB Maastricht.

Names such as 'Death book', 'Death register' or 'Deceased Brothers' would be considered as too blunt nowadays. In earlier days, however, such direct language was not be unusual. On the title page of this register of the deceased of the Sint-Matthias parish, death is pictured with hourglass and sicle in hand. On the left side, a old man's skeleton, complete with beard, holding the apple of sin and the Latin expression meaning "the evanescence tempts". Written at the bottom of the page: "death is the final destination".

The smallest book: Den Kleynen Maestrichter pocket-almanac, Maastricht, Jacob Lekens, 1766. Almanac collection RAL (State Archives of Limburg).

The smallest book

Den Kleynen Maestrichter pocket-almanac, Maastricht, Jacob Lekens, 1766. Almanac collection RAL (State Archives of Limburg).

This smallest almanac of Maastricht, printed by Jacob Lekens, doesn't only have delicate binding, but also an artistically decorated cover. The little book contains the exlibris of Petrus Renier from Wassenaar-Warmond. This Baron of Wassenaar (1708-1772) was appointed dean of the Sint-Servaas canons in 1733 by the State General and thereby required to pay thirty-thousand guilders. He passed away in Maastricht and was burried in the central nave of the Sint-Servaas Church. The Van Wassenaar-Warmond family was a Catholic family of South-Holland nobility, that raised two more members of the Sint-Servaas canons. Jan Martinus (1715-1784), the younger brother of Petrus Renier, was a canon. Thomas Willem Jacob (1740-1817) was the last dean of Sint Servaas.

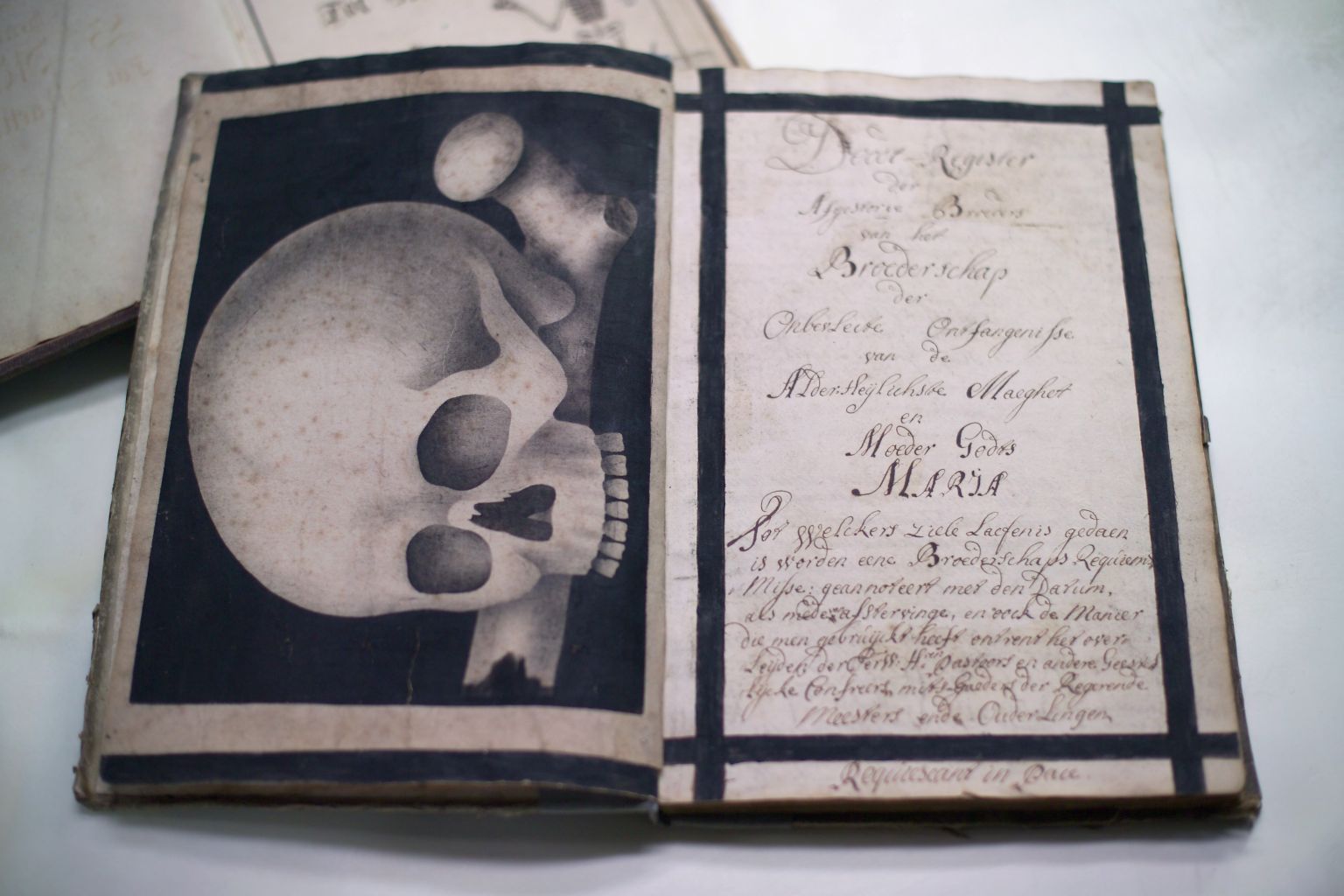

'Suspending the case...': Sack of proceedings, 1782-1788. Brabant 'deciding commissioners' archive Maastricht.

'Suspending the case...'

Sack of proceedings, 1782-1788. Brabant 'deciding commissioners' archive Maastricht.

The proceedings that took place in Maastricht before the 'deciding commissioners' were prepared by the 'instructing commissioners'. Next, the papers from such a case would be stored in a linnen sack and hung from a hook for the deciding commissioners, who were required to indicate a sentence. This is where the expression comes from, 'hangende het proces...' or 'suspending the case' (literally and figuratively). Even after the case was settled, the proceedings were still kept in sacks with the names of the parties involved and the year on them. Most of these sacks were of the same size and shape. For the really elaborate cases, such as that of the monastic order versus the pastors in 1782, a larger sack was needed, like a smaller-sized one used for coal.

Ever-present (3): Freemason's diploma and apron, around 1800.

Ever-present (3)

Freemason's diploma and apron, around 1800.

Once again a skull, only this time it appears on an apron that was used for Freemason rituals. The compass and three-cornered tear are symbols typical of Freemasonry. The first lodge was built in1745, called La Concorde. The first lodge for citizens was La Constance, founded in 1750 and drew inspiration from Liege and France . In 1763, the second civilian lodge was established, La Persévérance. Contrary to La Constance, this lodge was inclined to the State and was devoted to the ‘Grote Loge der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden’ or the Great Lodge of the Seven United Netherlands in The Hague. La Persévérance reached it's full glory around 1870 and still exists today. The other lodges disappeared in the French Period.

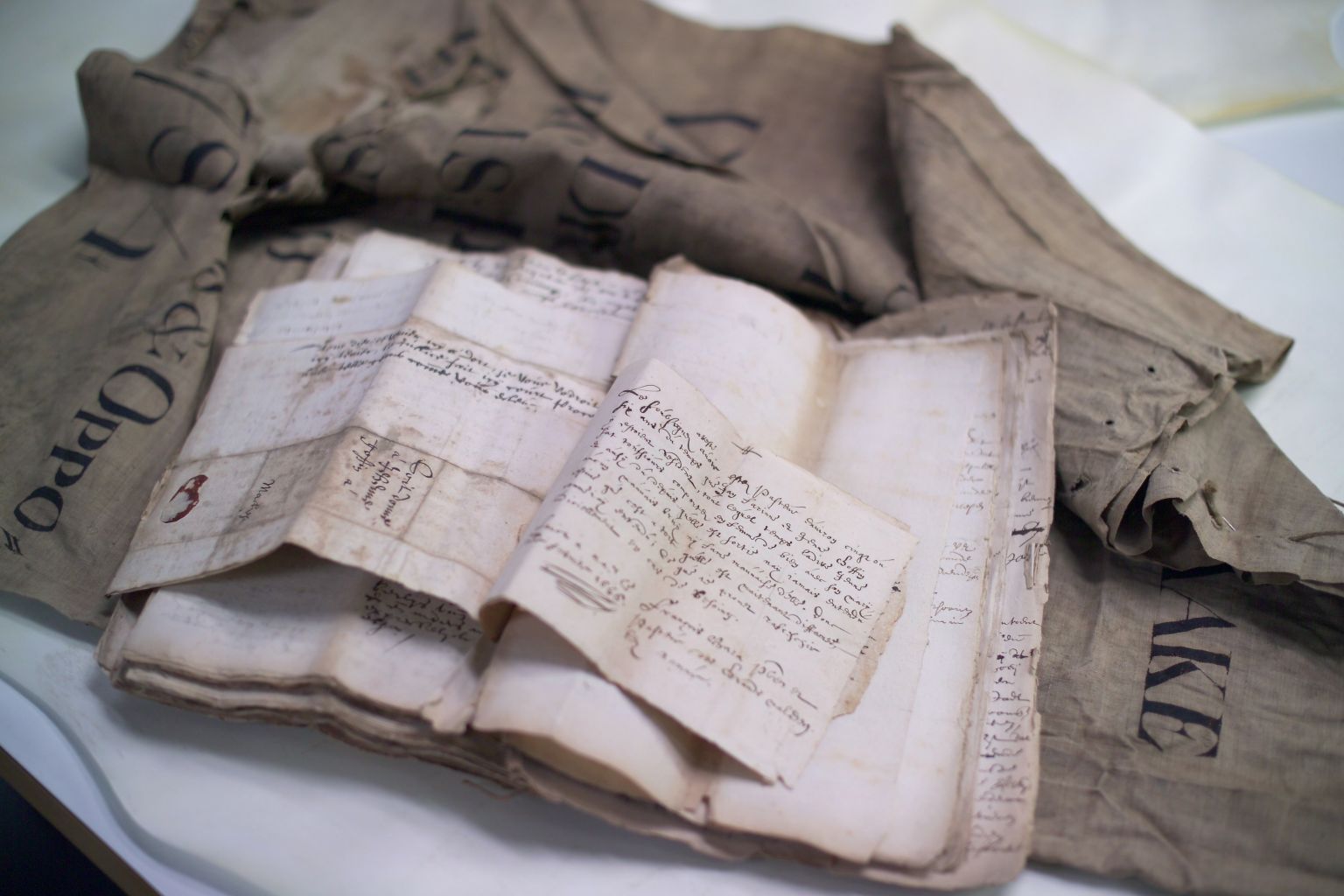

Soldier under Napoleon: Soldier's letter, 1813. Handwriting collection RAL.

Soldier under Napoleon

Soldier's letter, 1813. Handwriting collection RAL.

From 1795 to 1814, the area that would later be known as Limburg was annexed by France. The northern part of this region belonged to the Department (province) of the Roer, the southern part, to the Department of the Nedermaas. In 1798, military service was introduced in France, meaning that young men in our province were required to serve in the French army. One of them, Matthias Banens, wrote this somewhat clumsy letter in the winter of 1813, just before leaving for Russia, from the Ecole Militaire in Paris to his aunt and uncle in Maastricht. The letterhead, in color, shows a soldier of the imperial guard. Pictured in medallion on either side, are the portraits of the emperor Napolean Bonaparte and his wife Joséphine de Beauharnais.

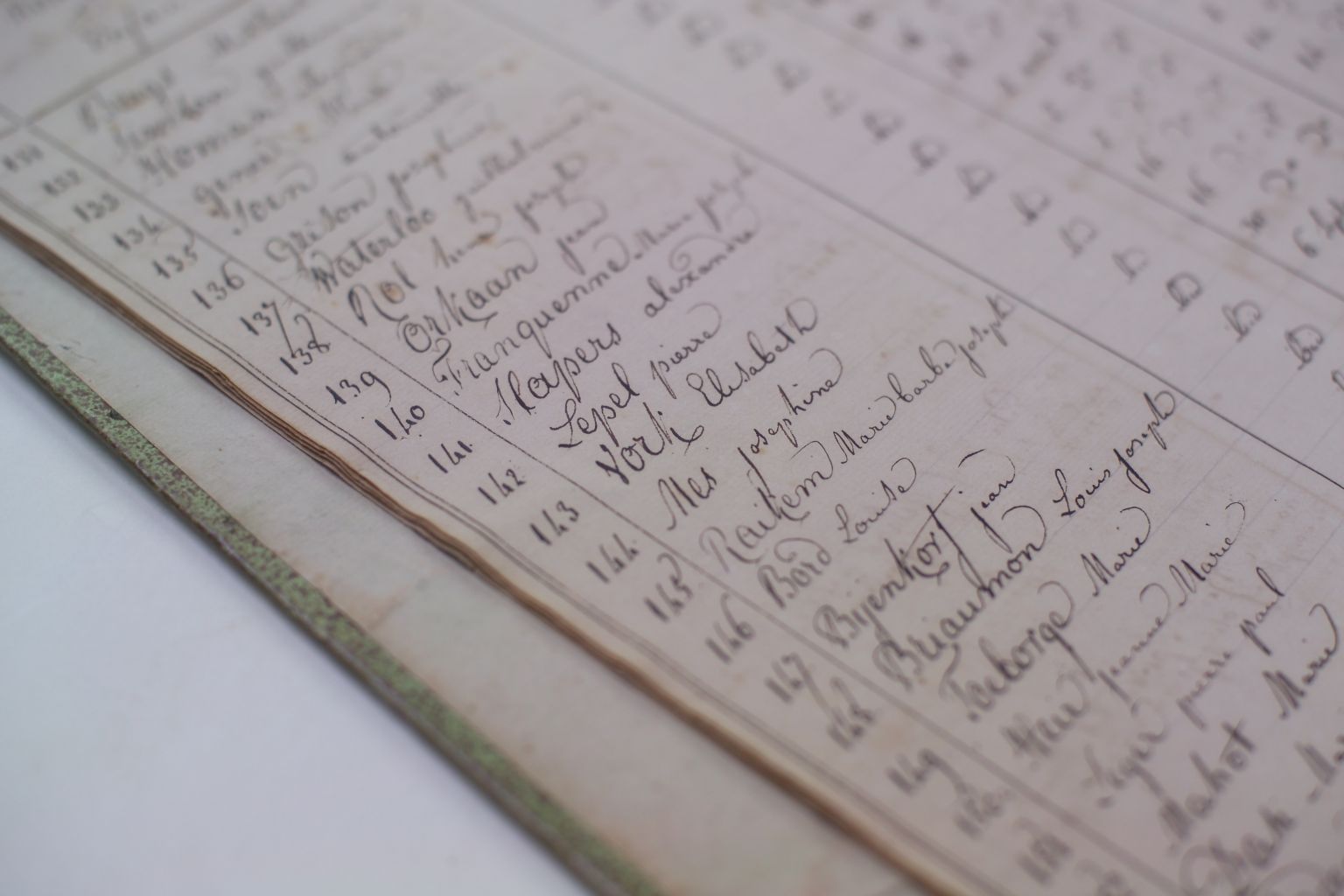

Spoon, fork, knife and plate: Foundling register, 1818-1830. Archives of charity organisations in Maastricht.

Spoon, fork, knife and plate

Foundling register, 1818-1830. Archives of charity organisations in Maastricht.

At the end of the eighteenth-century, the French government introduced civil registration. From then on, the first and official last name of every citizen was registered. For foundlings without a last name, this created a problem. Registration with only a first name was not possible. In the foundling house of Maastricht at the start of the nineteenth-century, the daughter of the landlord thought up an entire series of surnames, where the circumstances in which the children were found often served as a source of inspiration. A child that was found with a bit of satin fabric received, for example, the name Joseph Satijn (meaning Satin). Franciscus Mist was left behind by his parents on a dung heap and Jean Orkaan (Hurricane) was discovered on a very windy day. The names 'Veldslag' (Battlefield) and 'Waterloo' refer to the remembrance of the battle of Waterloo. Henri Joseph Rol was probably found in the 'rol' (cylindrical cavity) of the foundling house, a kind of night safe where a foundling could be left anonymously. When the inspiration seemed to be completely exhausted, the following series of names was created: Pierre Lepel (Spoon) - Elisabeth Vork (Fork) - Josephine Mes (Knife) - Louise Bord (Plate). All of these invented names were recorded officially in the citizen register of the municipality and also in the foundling register pictured here.

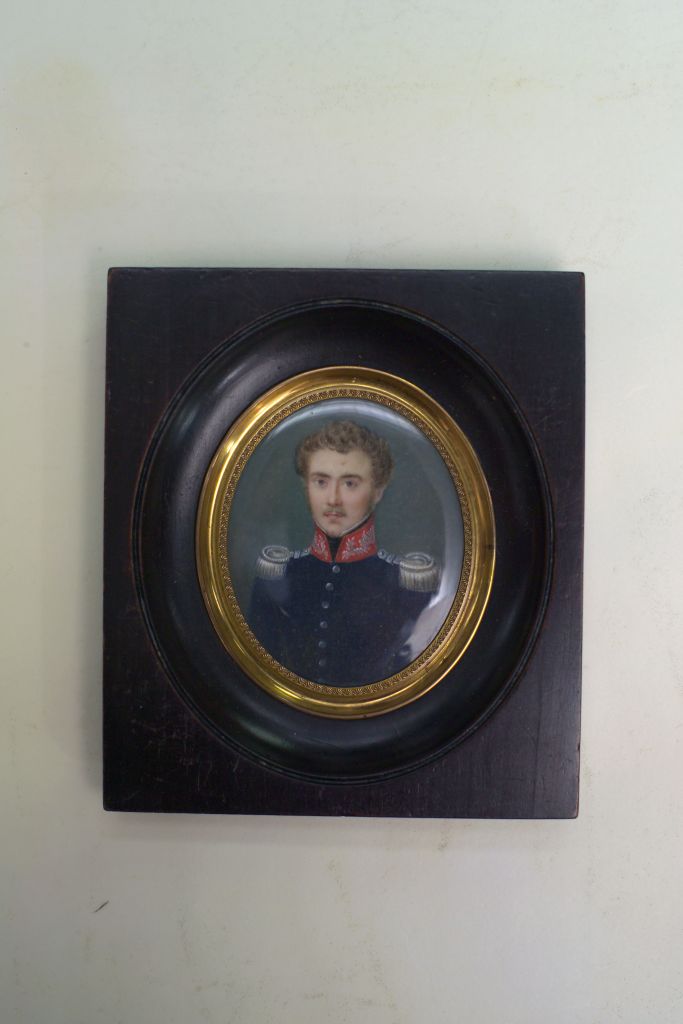

A mini portrait: Family archive Behr.

A mini portrait

A mini portrait

The archive of the Behr family of Maastricht contains in adition to archive pieces and photos, also paintings and miniatures, among which this minature portrait of Charles Behr (1800-1853) estimated to be from around 1820. Charles was wed to Clara Dubois in his first marriage, and later, after her death to her sister Pauline, who were both from Luik. At the height of the struggle for Belgian Independence, he as commanding officer of the troops in Luik, is said to have reacted well to feelings that ran high in the city. As a result of these winnings, after his death, his wife and children were exalted to a position of royalty by King Leopold II in 1877. In the archive, only the royal letter from his daughter Francoise Pauline has been kept. This deed was written on parchment and is safeguarded in a special small suitcase.

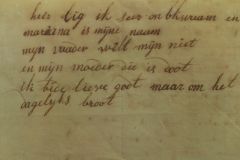

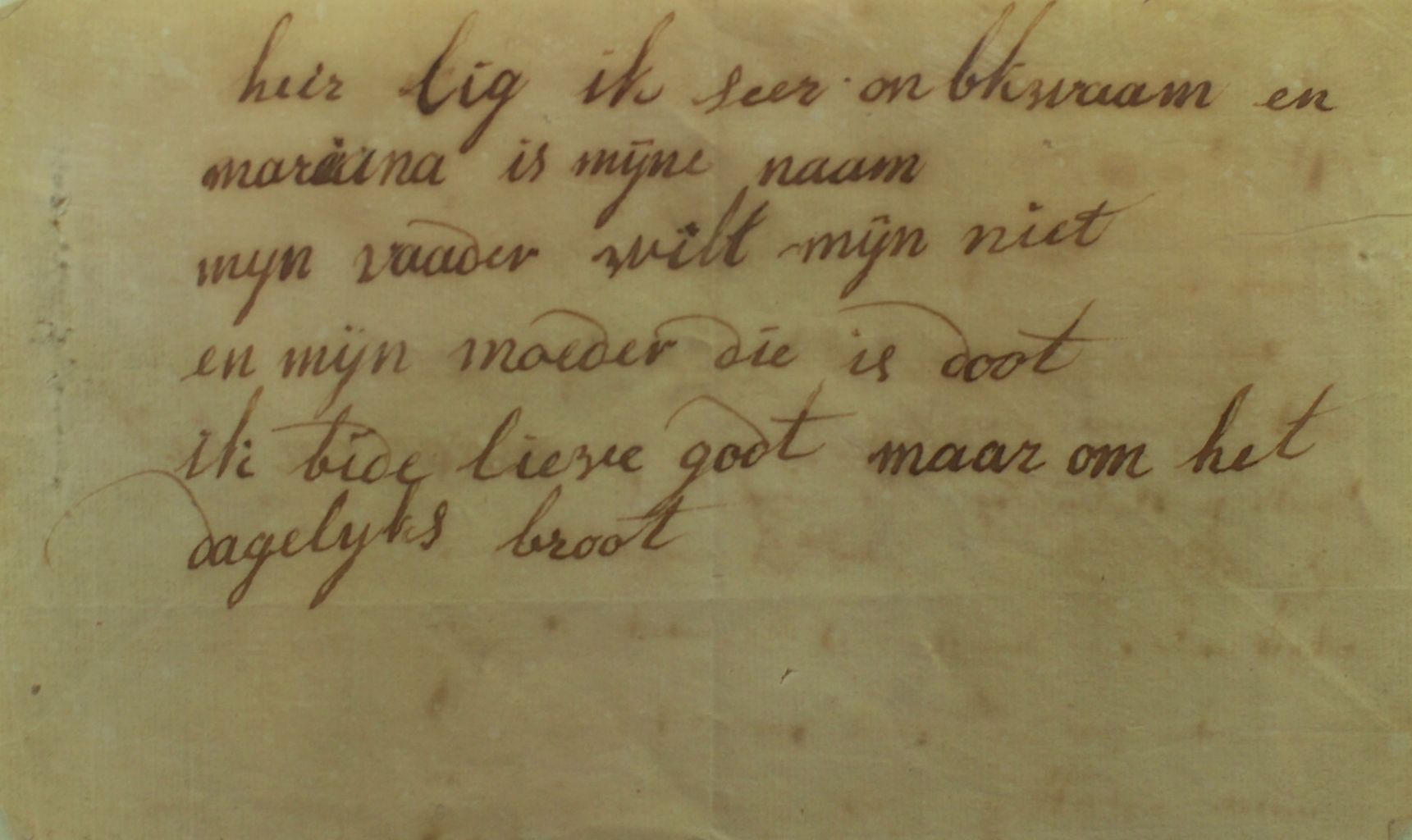

Maria Anna Dicht: Enclosure of a foundling deed, 1820. Archive of the civil Registry of Maastricht, enclosures births.

Maria Anna Dicht

Enclosure of a foundling deed, 1820. Archive of the civil Registry of Maastricht, enclosures births.

One of the nameless foundlings, for whom a name was invented, had the first name Maria Anna. She was named 'Dicht', meaning Poem in english, after this verse that was found with her. Below the original dutch text and its approximate translation in english:

Hier lig ik seer onbekwaam en

Marianna is mijn naam

mijn vader wilt mijn niet

en mijn moeder die is doot

ik bide lieve godt maar om het

dagelijks broot

Here I lay a helpless babe

Marianna is my name

my father does not want me

and my mother she is dead

i pray dear god for the daily bread

The oldest photo: Daguerotype of the castle of Neercanne near Maastricht, 1844. Photo collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

The oldest photo

Daguerotype of the castle of Neercanne near Maastricht, 1844. Photo collection GAM.

1827 was the year of the first camera-made, photographic image was made that was not subject to fading. Only in 1839 did the Frenchman Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre discover how to develop a handy procedure where a print was possible on a silver-coated copper plate, the so-called daguerrotype. This knowledge spread through Paris and beyond, finally reaching the photographers of Luik and Aachen and eventually Maastricht. The oldest photographic image of an subject from Mastricht is - to the best of our knowledge - this one, a daguerreotype of the castle of Neercanne (picture is a mirror-image) dating from 1844.

Maastricht in the year 1865: Panorama of Maastricht, Th. Weijnen, 1865. Photo collection GAM (City Archives of Maastricht).

Maastricht in the year 1865

Panorama of Maastricht, Th. Weijnen, 1865. Photo collection GAM.

Photographer Theodor Weijnen took this photo from the tower of the Dinghuis. The high, steep rooftops are typical to Maastricht. To the right, the street, that is called 'Grote Staat'. Centered in the foreground is the side wall of the house 'de Libaert' (the local word for leopard, or 'Luipaard' in dutch), that was next to the 'Landscroon'. Both had to make way later for the building of the Vroom & Dreesmann department store. Before the completion of the City Hall on the Market in 1664, the magistrate resided in these two houses. In the background of the picture, the towers of the Sint Jan and, the - then still in Baroque style from before the restoration by Pierre Cuypers - Sint Servaas.

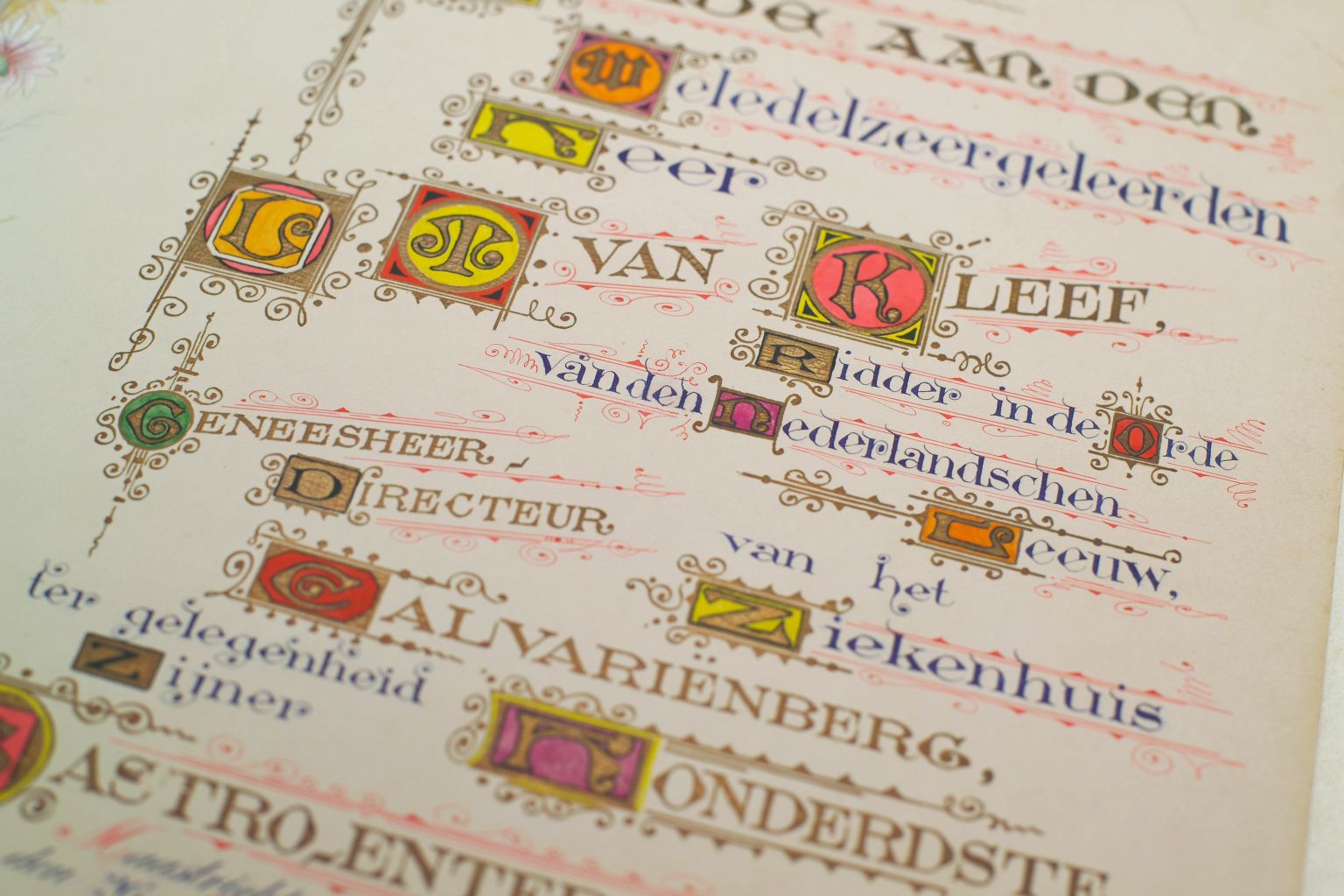

Operation succesful: Memorial book doctor Van Kleef, 1901. Archives of charity insttutions in Maastricht.

Operation succesful

Memorial book doctor Van Kleef, 1901. Archives of charity insttutions in Maastricht.

Doctor Lambertus Theodorus van Kleef (1846-1928) was medical superintendent of the former Calvariënberg hospital in Maastricht. As a scientist, he paved the way by experimenting with x-ray research and also by the stomach operations he was well-known for in the medical world at that time. To celebrate his hundredth operation in 1901, he was given a memorial book with this exuberantly scripted, calligraphy title page pictured here. The book is divided into columns giving information about each and every operation he performed, from the first up to the hundredth. Also described, is the progress of the patients after the operation and in the last column, a final notation of death or recovery. The thank you letters Van Kleef received from his cured patients were pasted next to the respective operation report. It is noticeable how few of these stomach-sufferers survived in the first fifty operations. Fortunately afterwards, the number of survivors increases significantly. In 1928, he himself died from a stomach ailment.